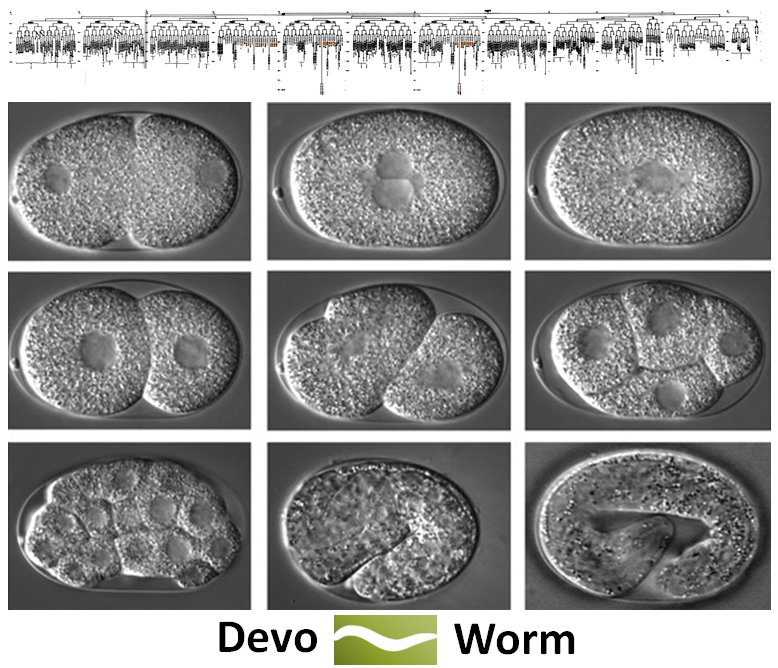

Now Announcing the DevoWorm Project

Over the past few months, myself and several colleagues (Stephen Larson, Dick Gordon, Steve McGrew, Mark Watts, and possibly Jack Tuszynski) have begun to hash out the details of a new project called DevoWorm. The project white paper, which lays out our goals and the associated technical details, can be found here. This is an extension of the existing OpenWorm project [1], which is an attempt to digitally emulate a relatively simple organism (C. elegans) from the cellular level up. In this case, emulation means a cell-by-cell representation and functional simulation in the spirit of open data movement.

Support the OpenWorm Kickstarter! Unfortunately, there is no DevoWorm Kickstarter (as of yet).

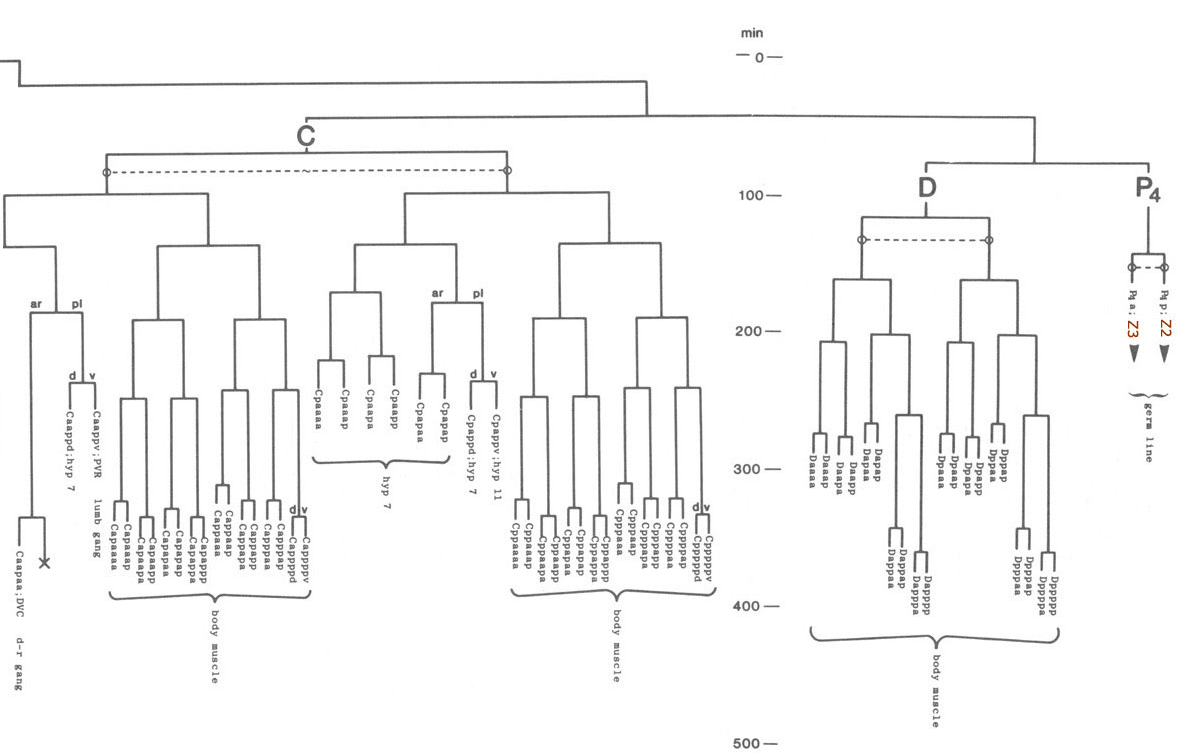

Whereas the OpenWorm project is focused on the C.elegans nervous system situated in an adult worm’s body [2], DevoWorm will focus on C.elegans development and the process of cellular differentiation. C. elegans is the optimal candidate system to study this process on a cell-by-cell basis because every cell in every developmental lineage is known and labelled. In the late 1970s and early 1980s [3], a team of scientists lead by John E. Sulston [4] constructed a cell lineage tree which organizes the developmental process by both planar location [5] and number of cell divisions.

A set of modules on a cell lineage tree, courtesy Sulston et.al [3]. The depth is defined by not only a certain number of cell divisions (each branching event), but how many minutes the process of cellular differentiation takes (sampled at 50 minute intervals). In C. elegans, each module corresponds with a specific function or tissue.

C. elegans provides a computationally tractable model for this kind of work. This species of worm consists of 956 adult cells, of which 850 of these cells are unique. Fifty of these unique cell pairs are equivalent, allowing for 2- and 4-way symmetry. The nervous system is a popular model for connectomics research, as the entire nervous system consists of just 300 cells and several thousand connections between them. In addition, C. elegans cellular differentiation is enabled through a mechanism called juxtacrine signaling, which differs from the endocrine signaling mechanisms of more complex Metazoans. The result is that cell fate is determined by their absolute position rather than by their environmental context. This has not only allowed for the lineage of each cell to be traced, but for each cell to be invariant in its identity from worm to worm. This invariance allows us to create a “parts list” based on the nomenclature of each cell in the organism [6].

Moving from lineage tree to morphology: the case of C. elegans intestinal morphogenesis (from blastomere to daughter cell pairs cells to adult intestine). COURTESY: Figure 2 in [7].

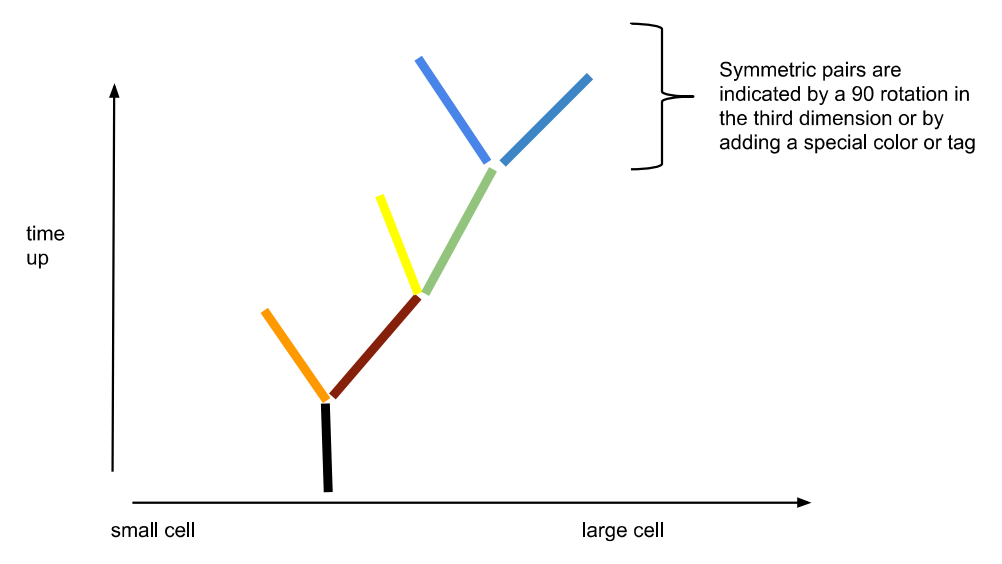

One bit of functionality that distinguishes the DevoWorm project from previous attempts at understanding C. elegans development is the re-interpretation of the lineage tree as a differentiation tree. How does this aid in our understanding of the process? Differentiation trees are similar to lineage trees in structure, but requires one to follow the logic of hierarchical differentiation theory [8] and allows for embryogenesis to be conceived of as a series of contracting and expanding waves.

A differentiation wave occurs through coordinated action between cells. It is initiated by a cell that expands or contracts to send a signal to its neighboring cell. This signal is sent through a cytoskeletal element at the apical end of the cell, which is otherwise known as a cell state splitter. When binary cell differentiation occurs, this structure exists in a metastable state [8]. As cells change their shape and interact with the cell state splitter of their neighbors, a genetic regulatory program is activated in the receiving cell. This can induce changes within the receiving cell itself, or initiate the receiving cell to send information in the same way to the next neighbor downstream. As this process propagates from cell to cell, this can result in both expansion and contraction cascades, which can serve to specify the fate of entire tissues.

An example of how C.elegans can be reinterpreted as a differentiation tree. COURTESY: Dr. Richard Gordon.

In the differentiation wave model, each cell has a decision to make: whether or not to participate in an expansion or contraction wave. Depending on their size, we can measure this binary decision through indicators such as cell size. This gives us bits of information, which in turn gives us a differentiation code for a certain volume of cells or tissue. In a differentiation tree, the distribution and persistence of these waves define the modules of development. While we have not directly observed these processes in C. elegans, it has been observed in axolotl embryos [9]. In addition, the theory of hierarchical differentiation predicts that this mechanism actively guides C. elegans embryogenesis.

So this can essentially be thought of as a theoretical re-interpretation of the lineage tree concept, with application to whole-organism simulation. The ultimate goal of the DevoWorm project is to create a simulation of highly-specified organismal development, where virtual ablations and other perturbations can be introduced at various stages of development. The outcomes transcend a biological organism’s ability to survive the treatment, and can give us important information about the plausibility of some phenotypes over others. At a future data, we would also like to characterize the functional genomics of C. elegans as a computational abstraction. This would provide us with even better resolution and allow us to ask more profound and fundamental questions regarding C. elegans embryogenesis.

UPDATE (7/15/2014): We have a new member of our group. I would like to welcome Tim Warrington, a graduate student who works on the genetics of C. elegans at Simon Fraser University.

UPDATE (10/14/2014): For more information on the origins of the OpenWorm project, please see: “A History and Pre-history of OpenWorm” (although it’s more of a timeline).

NOTES:

[1] Palyanov, A., Khayrulin, S., Larson, S.D., and Dibert, A. Towards a virtual C. elegans: A framework for simulation and visualization of the neuromuscular system in a 3D physical environment. In Silico Biology, 11(3-4), 137-147 (2012).

[2] For more on the project description and technical details, please see: OpenWorm. Artificial Brains: the quest to build sentient machines. August 14 (2012).

[3] The OpenWorm (and by extension DevoWorm) data structures are based on taxonomic work from the following papers:

a) Sulston, J.E. and Horvitz, H.R. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology, 56, 110-156 (1977).

b) Sulston, J.E., Albertson, D.G., and Thomson, J.N. The Caenorhabditis elegans Male: postembryonic development of non-gonadal structures. Developmental Biology, 78, 542-576 (1980).

c) Sulston, J.E., Schierenberg, E., White, J.G., and Thomson, J.N. The Embryonic Cell Lineage of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology, 100, 64-119 (1983).

[4] Sulston, J.E. C. elegans: the cell lineage and beyond. Nobel Lecture, December 8 (2002).

[5] Planar location is a location in a three-dimensional matrix: anterior-posterior (x), left-right (y), and dorsal-ventral (z).

[6] Sulston, J.E. and White, J.E. C. elegans cell list. Worm Atlas (2014).

[7] McGhee, J.D. The C. elegans Intestine. In “WormBook: Developmental Control”, C. elegans Research Community (eds.), WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.133.1 (2007).

[8] Gordon, R. The Hierarchical Genome and Differentiation Waves: novel unification of development, genetics and evolution. World Scientific, London (1999).

[9] Gordon, R. and Bjorklund, N.K. How to observe surface contraction waves on axolotl embryos. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 40, 913-914 (1996).

Posted by Bradly Alicea