C. elegans as an Evolutionary Model

In the past year, I have been starting to use the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm) as a model organism. Not only have I helped to establish the DevoWorm project, I am also starting to engage with C. elegans in a wet-lab setting. As a consequence, I am learning about multiple facets of C. elegans biology. C. elegans is a well-established model organism, having well-characterized neural and developmental systems. The nervous system contains just 302 cells, with a full accounting of the connectome (synaptic connections) [1]. The developmental system is also well-characterized, with a lineage tree [2] having been worked out for the entire organism. While a lineage tree relies upon deterministic mechanisms (and thus cannot be applied to organisms such as Mammals), it does provide us with a clear accounting of cell differentiation and organ formation during development. Thus, C. elegans is a tractable model for whole-organism investigations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Anatomy of the adult hermaphrodite. COURTESY: WormAtlas.

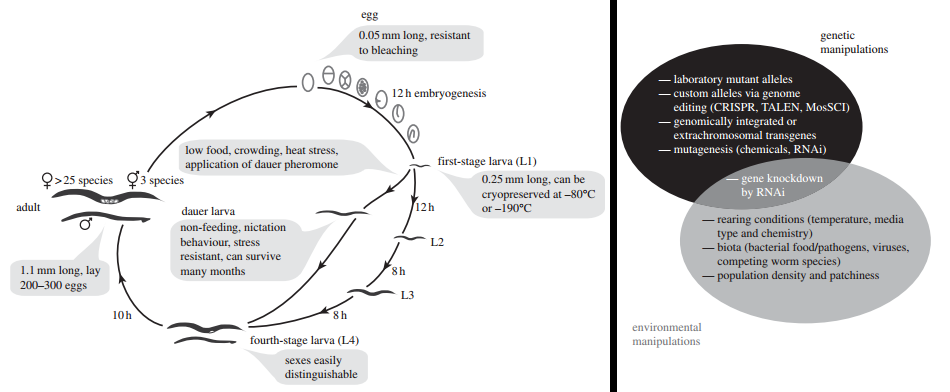

But what about evolution? At first pass, it seems as though asking evolutionary questions is not a tractable feature of roundworm biology. Nevertheless, we can use this worm to answer several outstanding questions in evolution [4]. I will use information from a recent review by Jeremy Gray and Asher Cutter [5] to discuss these potential research advances (Figure 2). The actual future applications of C. elegans as an evolutionary model might turn out to investigate other issues. As it turns out, the roundworm provides a happy medium between more traditional models of experimental evolution (microbes) and complex organisms with long generation times (humans). While C. elegans have a relatively short generation time (~50 hours), they also have complex phenotypes with organs.

Figure 2. The life cycle and means of experimental manipulation for evolution experiments. COURTESY: Figure 1 in [5].

The most common means of experimental evolution proposed in [5] is the mutation accumulation (MA) approach. MA may also serve as a weak factor in determining life-history traits in a species [6]. In experimental evolution, the MA approach allows us to observe the role of mutational variation in evolution. One way to apply this method might be to manipulate a single gene (using directed mutagenesis, gene editing, or RNAi – see Figure 2) and then place it in a genetic background. Rather than waiting for a series of mutations to emerge in a population, mutation is induced to maximize the variation upon which evolution can act upon [7].

Another means of experimental evolution discussed in [5] is co-evolution between worms and pathogens. This can done by culturing worms in ecological context over several generations. One prediction involves the evolution of tradeoffs observed in already co-evolved relationships such as C. elegans growth rate and pathogenic resistance [8]. A secondary means of understanding the ecology of evolution involves introducing environmental fragmentation through introducing spatial variation (physical barriers or agar gradients) on a culture dish. This can produce to genetic bottlenecks and other effects related to population structure and neutral processes.

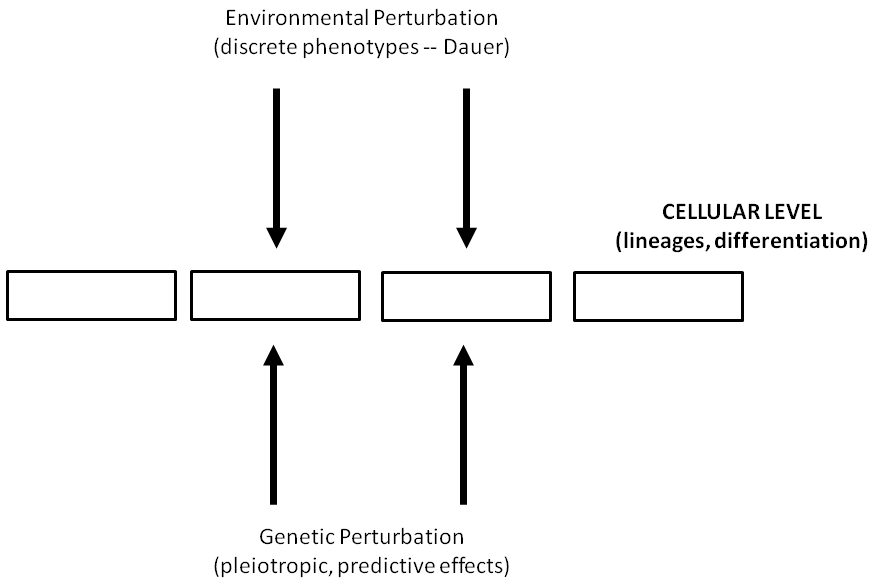

A third strategy discussed in [5] involves examining different reproductive strategies and degrees of adaptability between species of Caenorhabditis. The latter topic might include a better understanding of how the degeneracy [9] of neuronal and genetic circuits that lead to observable behaviors and phenotypes evolves. Yet there is also great potential for C. elegans to be used as an eco-evo-devo [10] model which integrates to response of environmental stimuli by cell and molecular mechanisms of development over evolutionary time (Figure 3). While I do not have plans on establishing my own C. elegans experimental evolution program in the near future, stay tuned.

Figure 3. A fledgling eco-evo-devo approach to C. elegans.

NOTES:

[1] Jarrell, T.A., Wang, Y., Bloniarz, A.E., Brittin, C.A., Xu, M., Thomson, J.N., Albertson, D.G. Hall, D.H., and Emmons, S.W. The Connectome of a Decision-Making Neural Network. Science, 337, 437-444 (2012).

Please also see The Connectome Project website.

[2] Sulston, J.E., Schierenberg, E., White, J.G., and Thomson, J.N. The Embryonic Cell Lineage of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology, 100, 64-119 (1983).

[3] Jovelin, R., Dey, A., Cutter, A.D. Fifteen Years of Evolutionary Genomics in Caenorhabditis elegans. eLS, doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0022897 (2013).

[4] For a review of Caenorhabditis phylogeny and evolutionary biology, please see: Fitch, D.H.A. and Thomas, W.K. Evolution. In “C. elegans II”, Chapter 29. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA (1997).

[5] Gray, J.C. and Cutter, A.D. Mainstreaming Caenorhabditis elegans in experimental evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 281, 20133055 (2014).

[6] Danko, M.J., Kozlowski, J., Vaupel, J.W., and Baudisch, A. Mutation Accumulation May Be a Minor Force in Shaping Life History Traits. PLoS One, 7(4), e34146 (2011).

[7] Thompson, O., Edgley, M., Strasbourger, P., Flibotte, S., Ewing, B., Adair, R., Au, V., Chaudhry, I., Fernando, L., Hutter, H., Kieffer, A., Lau, J., Lee, N., Miller, A., Raymant, G., Shen, B., Shendure, J., Taylor, J., Turner, E.H., Hillier, L.W., Moerman, D.G., and Waterston, R.H. The million mutation project: a new approach to genetics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Research, 23(10), 1749-1762 (2013).

[8] Schulte, R.D., Makus, C., Hasert, B., Michiels, N.K., and Schulenburg, H. Multiple reciprocal adaptations and rapid genetic change upon experimental coevolution of an animal host and its microbial parasite. PNAS USA, 107, 7359 –7364 (2010).

[9] Degeneracy involves structurally different elements (such as functional neuronal networks) that converge upon the same output. An example of this within C. elegans: Trojanowski, N.F., Padovan-Merhar, O., Raizen, D.M. and Fang-Yen, C. Neural and genetic degeneracy underlies Caenorhabditis elegans feeding behavior. Journal of Neurophysiology, 112, 951-961 (2014).

[10] Abouheif, E., Fave, M.J., Ibarraran-Viniegra, A.S., Lesoway, M.P., Rafiqi, A.M., and Rajakumar, R. Eco-evo-devo: the time has come. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 781, 107-125 (2014).

Posted by Bradly Alicea