Ancient Embryogenesis and Evolutionary Origins

“Darwin as an Embryo”. In this case, Neoteny really does recapitulates Phylogeny COURTESY: Stable Diffusion.

For this year’s delayed Darwin Day post, I will present some of the latest work on ancient embryos which we have been discussing in the DevoWorm group meetings. While this is by no means a complete review, we will discuss the earliest fossil evidence for eggs, embryos, and nervous systems (in animals, not plants), in addition to the conditions that lead to their emergence. In short, how did we get to embryos from a universal common ancestor with bacteria and archebacteria, and why do only different types of Eukaryotes (plants, radial symmetrical Metazoans, and bilateral Metazoans) have embryos?

Tree of Life (genome tree) from Hug et.al [1] with three domains. Click to enlarge.

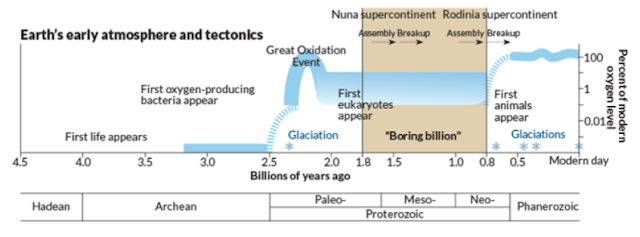

The ecological states of early Earth. COURTESY: J. Hirshfeld/Wikimedia. Click to enlarge.

We begin in the Cambrian, where the firs bilaterian appeared around 600 million years ago, approximately 70-80 million years before the Cambrian explosion [2]. In between the emergence of bilaterians, several key innovations occurred that suggests the origins of embryos and egg-laying. The first are the presence of fossilized burrows [2] for egg-laying behaviors. By the end of the Cambrian explosion, early pancrustecean arthropod species were possibly subject to life-history tradeoffs related to clutch size [3]. Another key innovation is direct evidence in the form of well-preserved multicellular structures from the period leading up to the Cambrian explosion that show a transition in cell geometry from a 2-cell stage to a cleavage stage [4]. As representative of a variety of ancestral algae species from the Doushantuo formation, these remains have not been connected to any particular adult form. However, they do demonstrate oogenesis and cleavage [2]. Finally, the functional genomics of developmental pattern formation emerged during this time [5]. This includes a ProtoHox cluster in ancestral cnidarians [6], Hox gene duplication [7], and an increase in body size and shape diversity alongside the advent of bilaterian bauplans [8]. Multiple Hox gene families may have served the role of promoting directed locomotion that in turn promoted active exploration of the environment [7].

Images of a potential early embryo, including the 2-cell and cleavage stages [from 4]. Click to enlarge.

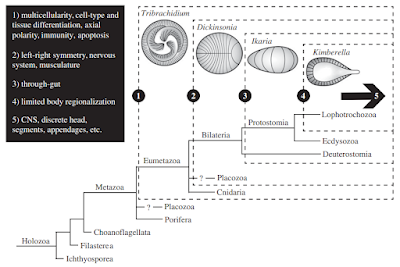

The Ediacaran (630-540 million years ago) has yielded a large number of potential embryonic forms. In the Ediacaran biota, we find a number of Metazoan remains with no clear phylogenetic position. However, Evans et.al [9] propose that early embryos evolved independently (with several origins) in the bilaterian clade. However, during this time, a number of general trends emerge that enabled modern bilaterian adult forms. As previously discussed, Multicellular structures with distinct cell types, axial polarity, and anatomical segmentation [10, 11] emerged during this time. Left-right symmetry was a related feature of these embryos [11]. So-called polarized elements [12] such as microtubules, flagella, and apical-to-basal orientation were all found soon after the last Eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA). The evolution and diversification of polarity proteins is consistent with this timeline [12]. Other organismal structures such as a gut, sub-specialization of the phenotype, and a nervous system with heads and appendages are also features of note. We will talk about the emergence of nervous systems later on.

Scenario for the origins of development in bilaterians from [9]. Click to enlarge.

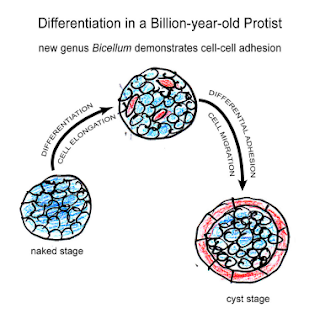

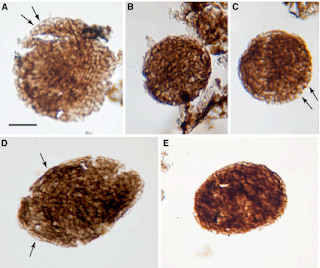

Bicellum brasieri is a 109 year old fossil holozoan that might provide the very earliest examples of modern embryos and embryogenesis [13]. Microfossils of Bicellum demonstrate morphogenesis in the form of cell-cell adhesion for different cell types, as well as differential layers of cells (driven by adhesion) which may be the precursors of tissue differentiation. This can be compared to the Doushantuo embryos from Precambrian China [14], and Caveasphera from 609 million years ago [15], which are perhaps the direct ancestors of Metazoan embryonic forms. These are the first examples of development proceeding within an enclosed space, enabled by cell adhesion similar to what is observed during gastrulation in modern embryos. Caveasphera in particular shows evidence of anatomical polarization (particularly polar aggregation), cell division events, and ingression [15]. This is informative but is not diagnostic of the Urmetazoan condition [16].

Graphical abstract and (top) palynological evidence of Bicellum brasieri (bottom) as shown in [13]. Epidermal layer (A and C), ellipsoid (D) and oblate (E) specimens Click to enlarge.

Since these pre-Cambrian explosion phenotypes are very simple, we can look to fossil evidence for much more complex embryo phenotypes in the late Cretaceous. Xing et.al [17] report on an in-ovo therapod dinosaur embryo, where the body is folded into an elongated egg. The authors are able to demonstrate how the fully formed head and legs are folded into different prehatching postures.

Graphical abstract showing developmental stages of Caveasphera [15]. Click to enlarge.

While the early phylogeny of nervous system origins is the very definition of a tangled tree [18], the first nervous systems coincide with the emergence of discrete body types in the Cambrian [19]. Brains emerged in part from the developmental toolkit responsible for patterning and segmentation [20]. This toolkit consists of genes and regulatory mechanisms that were co-opted for the development of excitable cells [21], synapses [22], and neuronal networks [2]. While the strongest evidence for early embryos only show evidence for bilaterian organization, radial symmetry is actually the basal condition for Metazoans [23]. Therefore, early embryos should yield at least two types of nervous system configurations that are observed in modern phenotypes: a centralized nervous system that converges in the head (the brains of bilaterians), and a distributed nervous system (the nerve nets of cnidarians). Centralized nervous systems originated from the mesoderm layer of triploblastic embryos, while distributed nervous systems are derived from the endoderm of diploblastic embryos. While there is a distinct literature on fossil radial embryos from China [24], there does not seem to be fossil evidence of germ layers formation and subsequent differentiation in any early embryos to date.

Image of Baby Yingliang (therapod dinosaur late-stage embryo) [17]. Click to enlarge.

But what happened before the earliest embryos (1000-650 million years ago)? What ecological conditions might have driven this innovation? One trigger may have been the great oxygenation event, which occurred in two stages: the first at 2.4 billion years ago, and the second at 950 million years ago. It was the second event that increased oxygen content to a level more resembling the present, and in turn drove diversification of distinct fungi, plants, and animals. It is of note that LECA (the last Eukaryotic common ancestor) lies well-beforehand [25]. The earliest embryos (or at least multicellular packings) might have resulted from selection pressure for retaining a low-oxygenation environment. But while these findings may lead to significant speculation, it seems that embryos are unique to Eukaryotic evolution, having no Bacterial or Archaebacterial counterpart despite evolving under the same conditions. It is most likely the interaction of genomic factors, developmental contingencies, and environmental conditions that ultimately lead to the emergence of embryos [26].

Phylogeny with evolution transitions from LUCA to embryos in plants and animals. Included are the two oxygenation events of Earth’s history. Transitions derived from Refs [14, 27-31]. Click to enlarge.

References

[1] Hug, L.A. et.al (2016). A new view of the tree of life. Nature Microbiology, 1, 16048.

[2] Valentine, J.W., Jablonski, D., and Erwin, D.H. (1999). Fossils, molecules and embryos: new perspectives on the Cambrian explosion. Development, 126, 851-859.

[3] Ou, Q., Vannier, J., Yang, X., Chen, A., Mai, H., Shu, D., Han, J., Fu, D., Wang, R., and Mayer, G. (2020). Evolutionary trade-off in reproduction of Cambrian arthropods. Science Advances, 6(18), doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz3376.

[4] Xiao, S., Zhang, Y. and Knoll, A. H. (1998). Three-dimensional preservation of algae and animal embryos in a Neoproterozoic phosphorite. Nature, 391, 553-558.

[5] Erwin, D.H. (2020). Origin of animal bodyplans: a view from the regulatory genome. Development, 147, dev182899.

[6] Chourrout, D. et al. (2006). Minimal ProtoHox cluster inferred from bilaterian and cnidarian Hox complements. Nature, 442, 684–687.

[7] Holland, P.W.H. (2015). Did homeobox gene duplications contribute to the Cambrian explosion? Zoological Letters, 1, 1.

[8] Zhuravlev, A.Y. and Wood, R. (2020). Dynamic and synchronous changes in metazoan body size during the Cambrian Explosion. Scientific Reports, 10, 6784.

[9] Evans, S.D., Droser, M.L., Erwin, D.H. (2021). Developmental processes in Ediacara macrofossils. Royal Society B, 288, 20203055.

[11] Finnerty, J.R., Pang, K., Burton, P., Paulson, D., and Martindale, M.Q. (2004). Origins of bilateral symmetry: Hox and Dpp expression in a sea anemone. Science, 304, 1335–1337.

[12] Brunet, T. and Booth, D.S. (2023). Cell polarity in the protist-to-animal transition. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, doi:10.1016/bs.ctdb.2023.03.001.

[13] Strother, P.K., Brasier, M.D., Wacey, D., Timpe, L., Saunders, M., and Wellman, C.H. (2021). A possible billion-year-old holozoan with differentiated multicellularity. Current Biology, 31, 1–8.

[14] First Embryos: Chen, J-Y., Bottjer, D.J., Li, G., Hadfield, M.G., Gao, F., Cameron, A.R., Zhang, C-Y., Xian, D-C., Tafforeau, P., Liao, X., and Yin, Z-J. (2009). Complex embryos displaying bilaterian characters from Precambrian Doushantuo phosphate deposits, Weng’an, Guizhou, China. PNAS, 106(45), 19056-19060.

[15] Yin, Z., Vargas, K., Cunningham, K., Bengtson, S., Zhu, M., Marone, F., and Donoghue, P. (2019). The Early Ediacaran Caveasphaera Foreshadows the Evolutionary Origin of Animal-like Embryology. Current Biology, 29, 4307–4314.

[16] Sebe-Pedros, A., Degnan, B.M., and Ruiz-Trillo, I. (2017). The origin of Metazoa: a unicellular perspective. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18, 498–512.

[17] Xing, L., Niu, K., Ma, W., Zelenitsky, D.K., Yang, T-R., and Brusatte, S.L. (2021). An exquisitely preserved in-ovo theropod dinosaur embryo sheds light on avian-like prehatching postures. iScience, 103516.

[18] Miller, G. (2009). On the Origin of The Nervous System. Science, 325(5936), 24-26.

[19] Erwin, D.H. (2020). Origin of animal bodyplans: a view from the regulatory genome. Development, 147, dev182899.

[20] Hartenstein, V. and Stollewerk, A. (2015). The evolution of early neurogenesis. Developmental Cell, 32, 390–407.

[21] Moroz, L.L. and Kohn, A.B. (2016). Independent origins of neurons and synapses: insights from ctenophores. Royal Society B, 371, 20150041.

[22] Moroz, L.L. (2021). Multiple Origins of Neurons From Secretory Cells. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 9, 669087.

[23] Ghysen, A. (2003). The origin and evolution of the nervous system. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 47(7-8), 555-562.

[24] Xian, X-F., Zhang, H-Q., Liu, Y-H., and Zhang, Y-N. (2019). Diverse radial symmetry among the Cambrian Fortunian fossil embryos from northern Sichuan and southern Shaanxi provinces, South China. Palaeoworld, 28(3), 225-233. AND Chang, S., Clausen, S., Zhang, L., Feng, Q., Steiner, M., Bottjer, D.J., Zhang, Y., Shi, M. (2018). New probable cnidarian fossils from the lower Cambrian of the Three Gorges area, South China, and their ecological implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 505, 150-166.

[25] McGrath, C. (2022). Highlight: Unraveling the Origins of LUCA and LECA on the Tree of Life. Genome Biology and Evolution, 14(6), evac072.

[26] Erwin, D.H. (2021). Developmental capacity and the early evolution of animals. Journal of the Geological Society, 178(5), jgs2020-245.

[27] Archaea: Gribaldo, S. and Brochier-Armanet, C. (2006). The Origin and Evolution of Archaea: a state of the art. Royal Society B, 361, 1007-1022.

[28] Great Oxygenation Event: Knoll, A.H.and Nowak, M.A. (2017). The Timetable of Evolution. Science Advances, 3, e1603076. AND Erwin, D.H. (2015). Early metazoan life: divergence, environment and ecology. Royal Society B, 370, 20150036.

[29] Fungi-Animal Common Ancestor: Phelps, C., Gburcik, V., Suslova, E., Dudek, P., Forafonov, F., Bot, N., MacLean, M., Fagan, R.J., and Picard, D. (2006). Fungi and animals may share a common ancestor to nuclear receptors. PNAS, 103(18), 7077–7081.

[30] LUCA: Dodd, MS, Papineau, D, Grenne, T et al. (5 more authors) (2017). Evidence for early life in Earth’s oldest hydrothermal vent precipitates. Nature, 543 (7643). pp. 60-64. AND Hassenkam, T., Andersson, M., Dalby, K., MacKensie, D.M.A., and Rosing, M.T. (2017). Elements of Eoarchean life trapped in mineral inclusions. Nature, 548, 78–81.

[31] Tree of Life: Feng, D-F., Cho, G., and Doolittle, R.F. (1997). Determining divergence times with a protein clock: Update and reevaluation. PNAS, 94, 13028-13033.

Posted by Bradly Alicea